Fallout

The repeated return of individuals into the criminal justice system has pressed Ohio courts to learn about trauma and its role in some actions that lead to legal trouble. By grasping how trauma disrupts lives, courts diminish conflicts during proceedings, curtail recidivism, and improve outcomes for the individuals and for the judicial system.

Fight, flight, or freeze.

They’re the instinctual responses humans have to real or perceived threats. It’s when someone grabs you unexpectedly from behind, and you swing around or yell. Or a car backfires, and a person nearby runs. It’s why, when a perpetrator pulls a gun in a store, a customer can’t move.

These are normal reactions to unusual events, said Brian L. Meyer, Ph.D., a specialist in post-traumatic stress and substance use disorders, at a recent Ohio Supreme Court conference. Distressing or life-threatening episodes can be traumatic. After a trauma, it’s typical for individuals to have short-term difficulties – maybe sleeplessness, or panicky feelings when there’s a loud noise. Then, if a person has an effective support system of family or friends and has learned healthy coping skills throughout life, he or she is likely to return to regular activities without any lingering consequences.

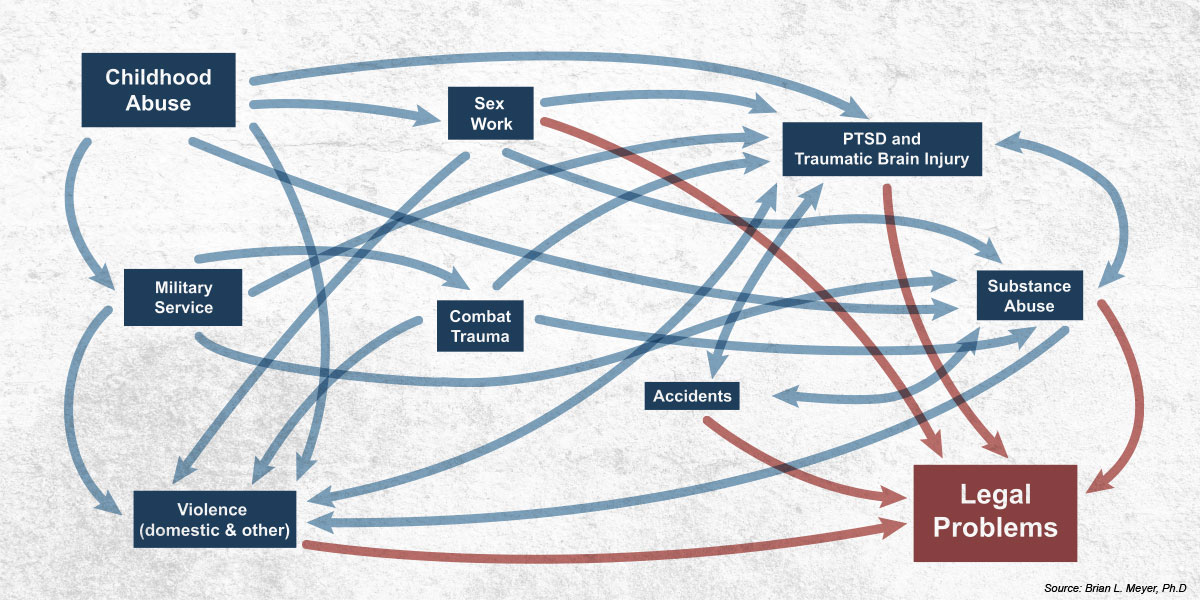

Sometimes, though, a person doesn’t bounce back from these experiences. That individual may develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or depression, or turn to alcohol or drugs, said Meyer, who works for the H. H. McGuire Veterans Administration Medical Center in Richmond, Virginia. When there’s a history of repeated or different types of traumas, problems often multiply. For people who are unable to cope safely, their actions may land them in trouble, and possibly in a courtroom.

Numerous courts in Ohio have found that a fast-moving day in the courthouse – one traditionally focused on punishment – does not address some complicated underlying issues carried by defendants, crime victims, or witnesses into the criminal justice system.

Human-Trafficking Court Relaxes Surroundings

The scene when the human-trafficking docket is on the schedule in Cleveland Municipal Court isn’t the typical one, with a prosecutor at one table, a defendant and lawyer at another, and a judge elevated on the bench. Instead, Judge Marilyn Cassidy dispenses with the robe, and the mood in the room is informal. Coffee and cookies are offered. A B.B. King song plays. Judge Cassidy walks around and personally welcomes each individual.

“We want to help to create a safe space,” she said.

The participants assigned to the program typically are charged with offenses, such as prostitution, solicitation, or petty theft, that stem from forced, compelled, or coerced commercial sex or labor activities.

H. H. McGuire Veterans Administration Medical Center

Karen Stanton, the docket coordinator, checks the court’s daily arraignments looking for signs that a person is ensnared in human trafficking. If an individual agrees to participate, the program offers an opportunity for treatment.

Before joining the human-trafficking court, Stanton, who also is a probation officer, said she was taught to be very authoritative and would tell those under her supervision, “Here are the rules, don’t do this, don’t do that.” Early on, though, Judge Cassidy, Stanton, and others attended training about trauma and its implications within the court setting. They’ve learned that trauma in its varied forms changes how the brain works.

Brain's Survival System Always Revving

Traumatic stress causes the amygdala – the part of the brain that responds to threats – to become overactivated, and decreases the activity in the prefrontal cortex, which governs judgment, risk evaluation, impulses, planning, and anticipation of consequences, Meyer said.

In simple terms, Meyer explained that for some who’ve experienced traumas, the fight, flight, or freeze responses never turn off, which prevents the thinking part of the brain from functioning properly. He said the brain stays stuck in survival mode.

A “simmering pot” is how Mandi Pierson described it. Pierson, a clinical social worker at the Mount Carmel Crime and Trauma Assistance Program in Columbus, has provided professional assistance and training to Franklin County’s human-trafficking court. She said with adrenaline flooding their systems all the time, those carrying around the effects of trauma don’t have as far to go before they boil over. This can cause difficulties in court.

“A negative response from an individual to court staff doesn’t necessarily mean the individual is refusing to comply,” Pierson said. “The reaction may be caused by a trauma response.”

She noted that “boiling over” doesn’t always equate to aggressive behaviors, like raised voices. Some people shut down, while others can’t complete necessary tasks.

She agreed that when laws or court rules are broken, the person must be confronted and held accountable.

Cleveland Municipal Court

She also suggested considering what it’s like to be in court. A person enters a room full of people they don’t know. The proceedings often move quickly. The judge, in the position of authority, can seem intimidating. Certainly, the process feels like that for an individual with little or no experience in court, Pierson noted. The bailiff may be uniformed, carry handcuffs, and be armed. Plus, Pierson pointed out, the defendant and others are waiting to hear from someone else what’s going to happen next in their lives.

For a person who hasn’t been able to sort out earlier traumas, the uncertainty of the unfolding events and the lack of time to build trust with anyone can trigger more primal, automatic responses, such as an outburst, or tears, or an attempt to leave the room, Pierson explained.

“The typical interventions by courts in these situations tend to be brief and don’t address the underlying trauma, keeping people in the same cycle,” she said. “When courts recognize that the traditional approaches don’t work for some people, it’s a game changer.”

What Doesn't Work, and What Does

“Because the fight, flight, or freeze response is constantly on for those who’ve been traumatized, we want to counteract that,” Judge Cassidy said. “The standard probation system is probably set up to fail. When people who’ve entered the justice system continually fail and return, we have to ask why.”

She noted that she spent several years pursuing cases for the county against those charged with crimes.

“I came from the prosecutor’s office, so changing how I viewed court was a huge leap for me,” she said. “Now I say to those in my court, ‘Let’s see if we can re-engage you.’”

Stanton also described a shift in mindset – from penalizing probation violations by sending someone to jail to looking more carefully at what’s happening to the person in the legal system.

“It’s hard for people who’ve been traumatized to follow the rules,” she said. “We’re trying to give them a way to succeed. It’s more realistic for courts to focus on what we can do with this population.”

It might be something simple, like having the bailiff set aside the handcuffs to help establish a feeling of safety and trust. It’s also ongoing positive reinforcement. Stanton said they celebrate the small successes, such as when a participant shows up for the court hearing or has a first meeting with a counselor. When someone flounders, Judge Cassidy said the court tries to address the issue. The court connects with community resources to assist participants with stumbling blocks – securing first month's rent for a place to live or identifying reliable transportation to a job, for example.

“We reinforce that they have value, that they are worthy of all the things life has to offer,” Judge Cassidy said.

Added Struggles for Those Serving in Military

“All courts should screen for trauma histories and PTSD specifically,” said Scott Tirocchi, division director of Justice for Vets, which is part of the National Association of Drug Court Professionals.

For those who’ve served in the armed forces, though, the military culture and training may drum up distinct issues set off when they return to civilian society. Military operations, missions, and combat can be stress-filled and dangerous, and often are life-threatening – the kinds of events that are traumatic. Tirocchi described a “warrior ethos,” which benefits members of the armed forces during their military career, but may foster some unhealthy behaviors when they leave.

“For example, those in the military are taught to suck up their problems and just drive on,” he said. “In some regard, this creates a dangerous psychological barrier that prevents a service member from asking for help when she or he really needs it.”

Meyer pointed out that military personnel also are drilled to be hypervigilant and to respond rapidly without thinking.

“Military training is designed to override fear and freeze responses,” he said.

Meyer and Tirocchi stressed that it’s essential for courts to understand traumas specific to deployment and military service. They also advocate for courts to continue to broaden their appreciation of how traumatic experiences can lead to legal issues, because the problem is pervasive.

Avoiding 'Misses in the Middle'

Areas Meyer identified where people with PTSD interact with the legal system: driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol, substance abuse, domestic violence, divorce, homelessness, violence, criminal behavior, child abuse, and juvenile delinquency.

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), “the experience of trauma among people with substance abuse and mental health disorders, especially those involved with the justice system, is so high as to be considered an almost universal experience.”

Justice for Vets

“If we want to reduce recidivism, then we need to address the roots of the problem, which are often traumatic,” Meyer said.

“It’s my observation that across the legal system, people are not widely informed about trauma,” Pierson said.

She shared that the steps needed to notice and address trauma’s role are viewed by many courts as detrimental to moving cases through the system. Courts are up against deadlines and often dealing with a high volume of cases, so taking more time feels counterintuitive, she noted.

“But if someone is consistently successful when a judge slows things down, then in the end it probably takes the same amount of time,” Pierson said. “It looks like it will take forever, but courts won’t have as many misses in the middle.”

Meyer added that understanding trauma is about treating people as human beings, not just as criminals.

“The question is less ‘What did you do and why?’ and more, ‘What happened to you that led you here?’” he said.

SAMHSA notes the actions that propelled many treatment court participants into the justice system reflect the way they cope with the physical and emotional impact of past trauma.

“This paradigm shift does not imply lack of responsibility for illegal behavior, but it does provide an opportunity to apply approaches that are most effective in promoting recovery and reducing recidivism,” states SAMHSA's 2013 materials on trauma-informed judicial practice. “Recognizing the impact of past trauma on treatment court participants does not mean that you must be both judge and treatment provider. Rather, trauma awareness is an opportunity to make small adjustments that improve judicial outcomes while minimizing avoidable challenges and conflict during and after hearings.”

Mental health professionals and court staff have seen many individuals gain control of their lives and become constructive members of the community when courts understand trauma and persevere to help people find new directions. It’s an outcome the experts and courts believe is worthwhile.