New Laws Unlock Possibilities for Fresh Start

Those seeking to move forward from criminal convictions can now ask courts to seal or expunge more records, building prospects for employment, housing, education, and a better future.

After graduating from college, Vicky was using drugs and became addicted. That led her to a series of wrong decisions in the 1990s, and she found herself in the criminal justice system. She was convicted of several offenses.

As the ’90s became the 2000s, Vicky, the name used to protect her privacy, joined a program for dealing with substance use problems. She became a mother. As she progressed with her recovery, though, her criminal record kept resurfacing. In those prior years struggling with addiction, Vicky had racked up convictions for a third-degree drug felony, seven or eight lower-level felony drug offenses, and many misdemeanors. Now as she tried to build a better life, she was being turned down for jobs when the employer ran a background check.

Vicky cobbled together work that paid by the hour, mostly at convenience stores. It wasn’t enough to support her family.

“She was being haunted by her bad choices earlier in her life,” said Robby Southers of the Franklin County Municipal Court Self Help Center.

Southers, the center’s managing attorney, met Vicky in April and heard her story. She visited the center after hearing about new laws in Ohio for sealing and expunging criminal records. For so many years Vicky had felt hopeless about her prospects to make a decent living in a job, or career, that could sustain her and her children. Because of her third-degree felony and the number of convictions, she hadn’t been eligible to seal the records. She wondered about the new laws.

Through the help center, a search was done to check her criminal record. Southers says the search showed nothing for the last two decades.

“It was completely clear – not even a speeding ticket since 1999,” he noted.

Because of how old all of Vicky’s convictions were, she was now permitted under the new laws to ask for her criminal records to be completely deleted, Southers said.

Legislation Reshapes Eligible Offenses and Waiting Times

The changes to sealing and expunging, which were part of a 499-page criminal justice overhaul enacted by the General Assembly, went into effect on April 4. In broad terms, it recalibrated which offenses can be sealed and expunged and what the waiting periods are.

The updates represent an evolution that may fundamentally alter options available to the estimated 994,000 Ohioans who are living with a felony conviction – approximately one in 11 adults. When people finish the sentence for a crime, they frequently face barrier upon barrier to getting a job, finding housing, and obtaining loans for further education. Research in 2018 from Policy Matters Ohio and the Ohio Justice & Policy Center found that one in four Ohio jobs are off limits to a person with a criminal conviction.

The opportunity to seal or expunge a record opens doors for individuals to reenter the workforce and society, earn a living wage, and make positive contributions. Securing employment, housing, and education also lessens the likelihood that a person with a criminal conviction will return to crime.

To understand the new laws, it’s essential to first know the distinctions between sealed versus expunged records in Ohio. Sealing limits most public access to the record. The record remains available, however, to specific groups and only for certain reasons. According to a recent Ohio Judicial College course, the groups that can see sealed records didn’t change with the new laws. Among those with access to sealed records are law enforcement officers and prosecutors when they need to determine whether a prior conviction would affect an expected criminal charge. Also, the person with the record and the person’s parole officer can view a sealed record. These records continue to be available for background investigations for employment with law enforcement agencies, corrections departments, or youth services departments and for background checks conducted by the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BCI).

With expungement, the records should no longer be available to anyone. A record that is expunged must be deleted, erased, or destroyed to make it permanently irretrievable. There is one exception – BCI can keep an expunged record for the sole purpose of determining whether someone is eligible to work in law enforcement.

There are a lot of updates with the new laws, so judges, magistrates, clerks, and other justice partners have been sorting through the legislation to correctly handle cases and assist people.

Records Allowed to Be Sealed Can Eventually Be Expunged

A key feature in the new laws is that any record that can be sealed can also now be expunged after an appropriate timeframe, Kevin Werner of the Ohio Justice & Policy Center explained.

“Many, many more Ohioans will be able to have old criminal records sealed. And when they get through the waiting periods, the records can be expunged,” Werner said at an Ohio State University Moritz College of Law webinar on the implications of the legislation.

“The vast improvements [made in the criminal justice bill] have made the statutes easier to navigate and understand,” Werner noted.

Before the new criminal justice laws took effect, a person who wanted to seal or expunge a record had to qualify as an “eligible offender.” The approach has been eliminated, a summary from the Ohio Judicial Conference explained. Instead, courts now must consider:

- Is the offense prohibited in state law from being sealed or expunged?

- Did the applicant wait the proper length of time before making the request?

Step 1: Is Crime Among Those That Cannot Be Sealed or Expunged?

The General Assembly reorganized the relevant statutes and identified offenses that are excluded from sealing or expunging. It grouped the offenses that cannot be sealed or expunged into six categories:

- First- and second-degree felonies, and three or more third-degree felonies.

- Felony offenses of violence that aren’t sexually oriented offenses.

- Sexually oriented crimes subject to registration requirements.

- Protection order violations and domestic violence offenses.

- Crimes involving young victims.

- Traffic offenses.

First- and Second-Degree Felonies, and Multiple Third-Degree Felonies: Convictions for felonies of the first degree, such as murder and some kidnappings, rapes, and aggravated vehicular homicides, can never be sealed or expunged. The same is true for second-degree felonies, which can be crimes like aggravated drug trafficking, aggravated theft, and identity fraud. This restriction is unchanged from prior law. When someone has three or more convictions for third-degree felonies, those offenses also cannot be sealed or expunged.

Felony Offenses of Violence: When someone is convicted for an offense of violence that is a felony, the record cannot be sealed or expunged. An “offense of violence” is defined in state law (R.C. 2901.01). (Some of the felonies in the first category above also fall into this group.) A guide recently developed by the Franklin County help center lists 40 felony offenses of violence that are ineligible for sealing or expunging – including arson, extortion, improperly discharging a firearm, trafficking in persons, SWATting (calls to send law enforcement under false pretenses to another person's address), and endangering children.

About one quarter of those 40 offenses can be either a felony or a misdemeanor. For people with a misdemeanor violent offense, the record is permitted to be sealed or expunged after the waiting periods. As explained at the recent Ohio Judicial College course, a conviction for a first-degree misdemeanor version of menacing by stalking, gross patient abuse, or witness intimidation could be sealed after the waiting period if approved by the court.

Sexually Oriented Offenses: A conviction for a sexually oriented offense cannot be sealed while the offender is subject to federal Sex Offender Registration and Notification (SORN) requirements. SORN is a system to notify the authorities and the public of convicted sex offenders in the community. While these convictions might qualify for sealing after the registration requirements expire, they can never be expunged.

Domestic Violence Crimes, and Protection Order Violations: Convictions for domestic violence or violating a protection order cannot be sealed, and therefore can’t be expunged either. A conviction under a substantially similar municipal ordinance also can’t be sealed.

Crimes Involving Young Victims: If a criminal conviction involves a victim under the age of 13, the record cannot be sealed or expunged. However, offenses for nonsupport or contributing to the nonsupport of children aren’t included in this category and can be sealed.

Traffic Offenses: Prohibited from ever being sealed or expunged are convictions for operating a vehicle under the influence of alcohol or drugs (OVI) and having physical control while under the influence. Convictions for nearly all other traffic offenses identified in the driver’s license, suspension, cancellation, and revocation laws also are ineligible. This prohibition extends to substantially similar municipal ordinances, according to the Judicial Conference.

If a conviction doesn’t fit into these categories, then a person can ask to seal the record after the waiting period. Southers said the most frequent requests are to seal drug convictions. Keep in mind that many crimes can be either felonies or misdemeanors, and someone can be convicted at varying levels of a felony or misdemeanor. There are important nuances in the categories of crimes excluded from sealing or expunging. Be sure to check with a help center or legal aid group to find out whether a specific record can be sealed or expunged. (See "Where to Find Help" below.)

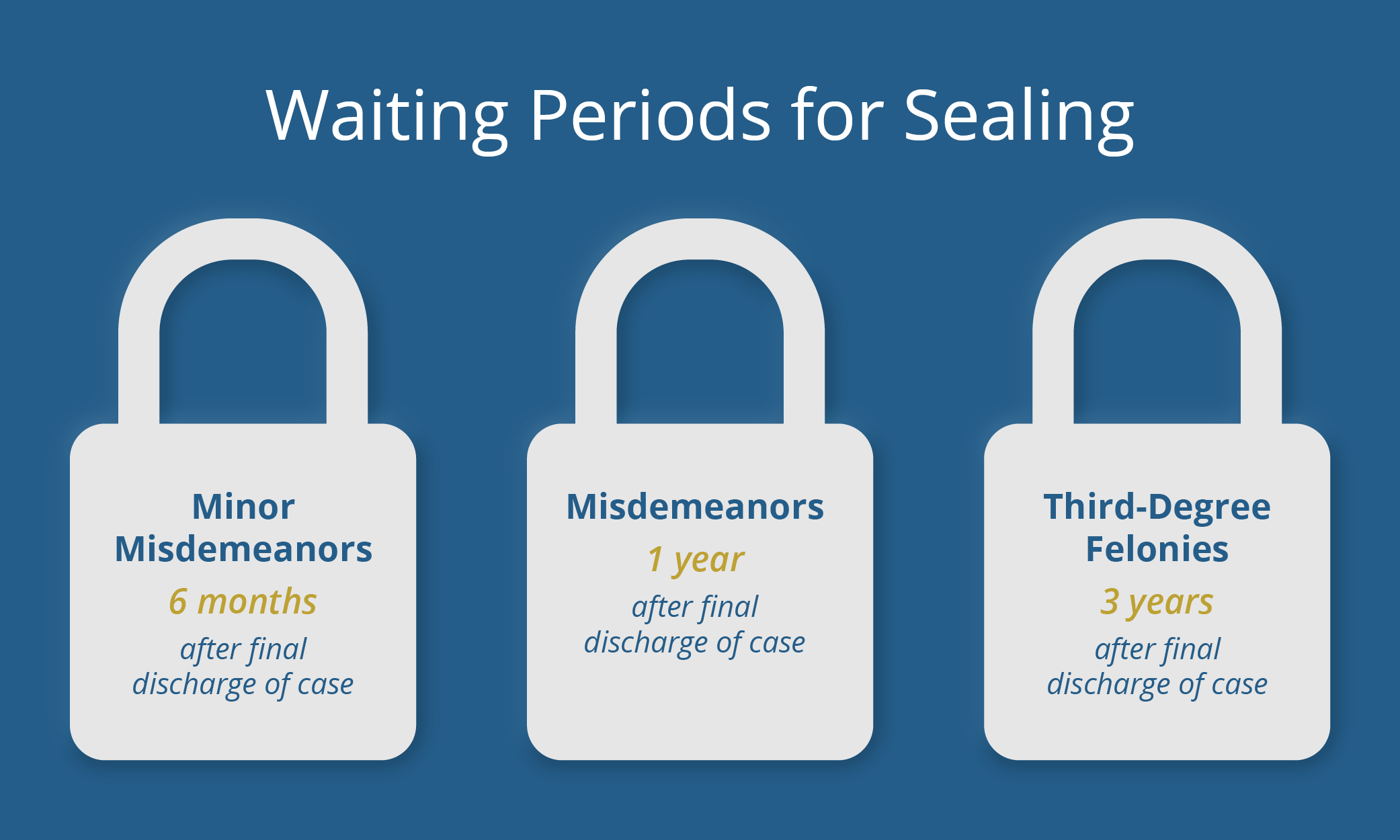

Step 2: Has Waiting Period After Conviction Been Met?

Whether the appropriate timeframe has passed is next in figuring out if a record can be sealed. Most waiting periods depend on when the “final discharge” of the case occurs. That’s when the person has: 1) completed any community service, jail, or prison sentence; 2) finished any probation or parole term; and 3) paid any fines. The updated waiting periods for sealing a record:

- Third-degree felonies, only one or two offenses: Three years after the final discharge of the case (except for theft in office).

- Fourth-degree felonies; fifth-degree felonies: One year after final discharge.

- Misdemeanors: One year after final discharge.

- Minor misdemeanors: Six months after final discharge.

- Convictions requiring sex offender registration: Five years after the registration duties end.

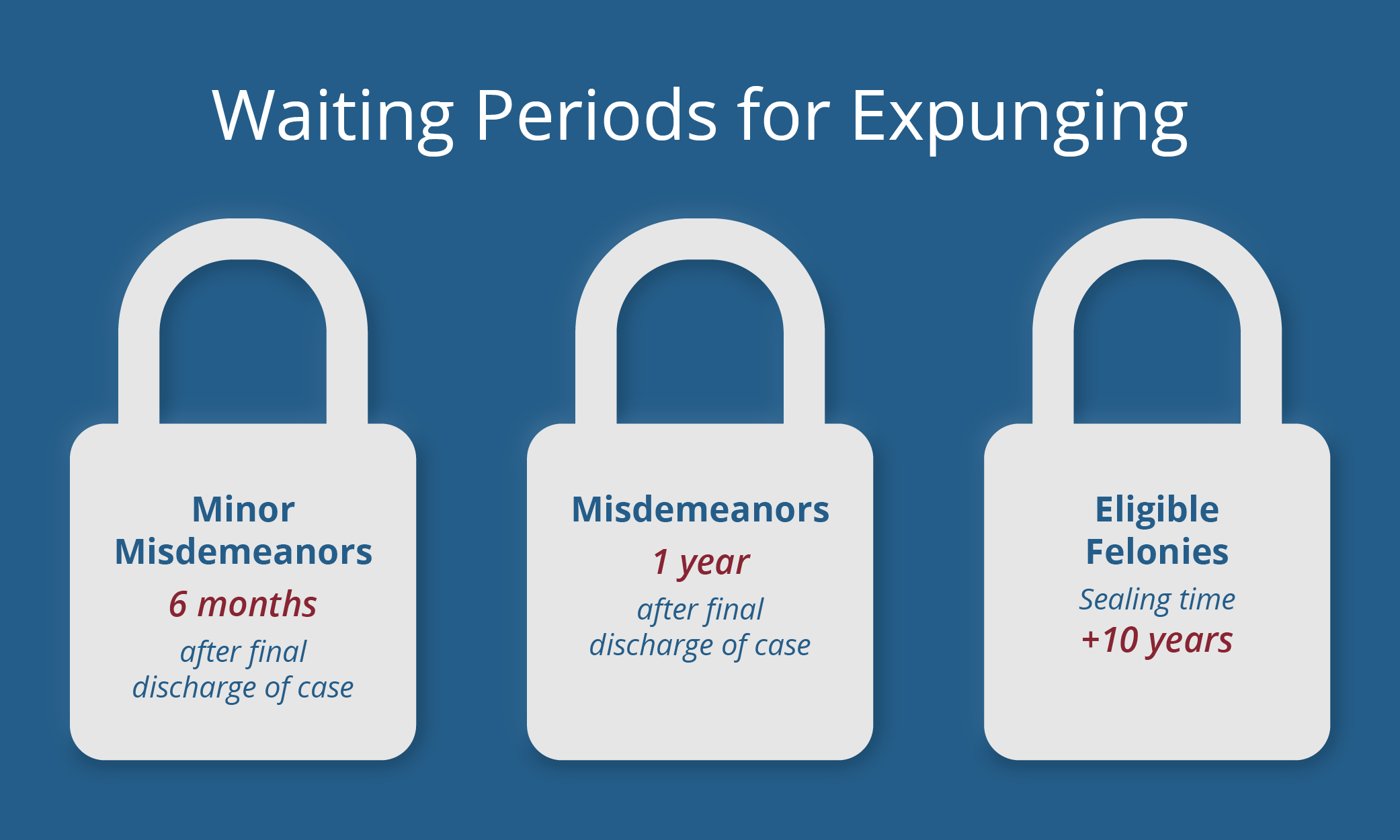

Expungements also have revised waiting times. A person can ask to expunge a record by following the same steps for sealing the record, but after the designated expungement waiting time has expired.

- Eligible felonies: The sealing waiting period plus 10 years.

- Misdemeanors: One year after final discharge of case.

- Minor misdemeanors: Six months after final discharge.

The experts point out that the criminal justice bill didn’t alter the prior expungement timelines for certain firearms offenses or for victims of human trafficking.

With waiting periods, though, some say more can be done. The Ohio Justice and Policy Center opposes waiting periods overall. Werner illustrates: A 22-year-old college student is convicted this year of hazing as a third-degree felony. If the student is sentenced to three years in prison and two years of community control, he will complete his sentence in 2028, at age 27. Once all fines are paid, he can request sealing three years later. (A third-degree felony can carry a fine of up to $10,000.) If he paid the fines at the time he finished his community control and he stays out of trouble, he will be 30 when he can first apply to seal the record. He can ask for the record to be expunged 10 years later, in 2041, at the age of 40.

“Waiting periods should not exist, or should be as short as possible,” Werner argued.

The Ohio Prosecuting Attorneys Association sees it differently. Lou Tobin, executive director, said the association finds the waiting periods, except the 10 years for felony expungements, to be “far too short.”

“We know from Bureau of Justice Statistics studies on recidivism that in excess of 60% of people are rearrested within three years of a release from prison,” Tobin noted. “We’re allowing them to seal records of multiple misdemeanors or felonies one year after their final discharge. So we’re giving the benefit of record sealing to a lot of people who are going to be rearrested.”

Court officials also discussed the effect of fines on waiting periods. Judge Matthew Reger of the Wood County Common Pleas Court said during the Judicial College course that fines, which are part of a criminal penalty, and restitution must be paid to conclude the case. Fines and restitution can keep a case open, preventing the final discharge of a case and possible sealing of the record.

However, if someone is unable to pay, the court can suspend the fines and discharge the case, Judge Reger noted. In that situation, he said the waiting period would begin from the date the fines are suspended. The judge also pointed out that court costs, which are charged for court operations, don’t play into when a case has been discharged.

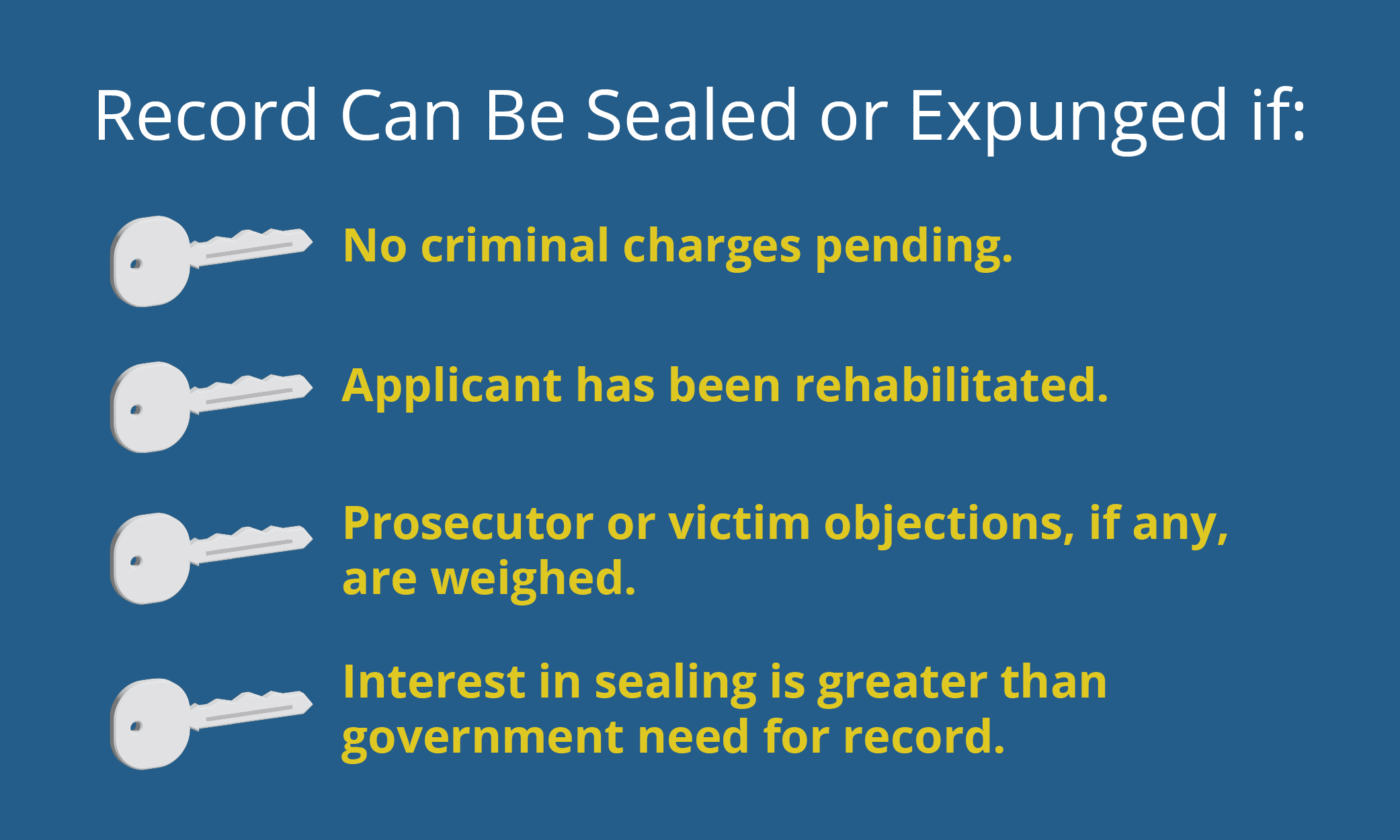

Courts Continue to Evaluate Sealing and Expungement Criteria

Before April 4, courts weighed several important factors when reviewing a sealing or expungement application. Retired Judge Patrick Carroll, who also spoke at the Judicial College course, pointed out that those factors remain in place. They include:

- Whether criminal charges are pending against the applicant.

- Whether the applicant has been rehabilitated to the court’s satisfaction. The courts have discretion in making this determination, usually based on a discussion with the applicant.

- Objections filed by the prosecutor or a victim.

- Interests in sealing the records versus legitimate government needs to maintain the records.

Judge Reger offered strategies that may help courts in implementing the changes made in the new laws. He suggested updating local court rules and defining procedures for expunging sealed records. The judge also emphasized the value of working together with other key players.

“One idea I have seen in other courts is a judicial collaboration committee, comprised of the clerk of courts, prosecutor, common pleas and municipal judges, sheriff, public defender, commissioners, and any others who are essential to the criminal justice process,” Judge Reger said. “This group discusses issues in the criminal justice system and seeks solutions, while understanding each person’s role in the system.”

Delaware County Clerk of Courts Natalie Fravel said her office has taken this approach, too, meeting with staff and partners to define the best workflow in light of the new laws. They also have relied on a bill analysis from the legislature for direction.

Fee Amounts Capped, Hearing Timelines Set

Two other notable changes – the fees charged to apply for sealing or expungement and the hearing schedule for the court considering the application. The fee to apply for sealing or expungement has been capped at $50 in the new laws, and applicants can submit the records from more than one case in a single $50 application. Of the $50, $30 is sent to the state treasury and $20 goes to the court’s local funding authority.

The cap is a big change, Judge Reger said. He recommends that judges talk to their clerk of court to figure out what adjustments are needed. In the prior law, courts were permitted to recover actual costs for mailing and other expenses, such as for court reporters, he said. The judge has heard the General Assembly is expected to revise the law again.

In Wood County, the judges decided not to alter their local rule about these fees until they know whether the legislature will alter the limit. For now, the court issued an administrative order to align with the law.

“Even if localities are allowed to recover actual costs, a judge always has the ability to waive those costs,” he adds, referring to the applicant’s ability to submit an affidavit of indigency if unable to afford the amounts.

Courts also now have an explicit deadline for holding hearings on sealing or expungement requests. Judge Reger noted that before the change in the laws, courts had no timeframe for setting a hearing. The statute stated, “Upon filing of an application … the court shall set a date for a hearing on the application.” Now the court must hold a hearing between 45 and 90 days from the date the application was filed. Any victims must be notified.

Prosecutors Can Initiate Sealing of Some Records

In the processes described above, the person who has a criminal record files the application themselves to have a record sealed or expunged. But the new laws authorize a novel procedure. Prosecutors now can initiate sealing or expungement of low-level drug offenses that are fourth-degree or minor misdemeanors, or the parallel offenses in municipal ordinances. At the Ohio State webinar, the panelists focused on marijuana possession convictions. These low-level offenses could also include improperly dispensing nitrous oxide, improperly purchasing pseudoephedrine products, and a few other crimes, said Tori Edwards, staff attorney at the Franklin County Municipal Court, in a follow-up email.

Besides pushing through the obstacles people encounter with these low-level convictions, the change will address frustrations expressed by employers and police departments, said Mark Griffin, director of law for the city of Cleveland. He explained at the webinar that employers are having difficulties finding workers, and expunging these offenses would make more people available for work. He added that police want to focus on violent crimes.

Tobin countered in an email that prosecutors can’t represent the government and seek to expunge people’s criminal records. This isn’t the prosecutor’s role in the justice system, he said.

In Cleveland, 4,000 cases have been identified for possible sealing or expunging under the prosecutor-driven process. The city prosecutors have discussed with the local judges, who suggested tackling in sets of 100 or so. Cleveland obtained a $10,000 grant for the filing fees and will notify those who may be helped by the project. Because the crimes are low-level drug offenses, there are rarely victims in the cases. But if there is a victim, the victim would be notified, Griffin said.

Edwards noted that the Columbus city attorney is moving forward on this process, too. More than 6,000 cases have been flagged for review.

Time Will Reveal Outcomes

Researchers who study sealing and expungement believe that policymakers and others will be interested in the effect – whether good or bad – of these changes. Gathering statewide data in Ohio’s decentralized law enforcement and court system, though, will make this an uphill climb, they noted.

Even if statewide data is hard to come by, Southers pointed out that multiple studies already show individuals with sealed records have greater economic mobility and are better able to live law-abiding lives. He also noted the uptick in requests for assistance in Franklin County. Only midway into the second quarter, the center has been helping an average of eight people every day with record sealing. That’s up from roughly five each day in the preceding year.

Whether people across all jurisdictions will have equal access to benefit from the reforms is a concern. Werner asked about the “legal services bandwidth” in Ohio to help all those who qualify to have their records sealed or expunged. More funding support for the changes is something the General Assembly may explore.

This year’s updates to the sealing and expungement laws reflect a forward momentum that can help people with records turn a corner toward a more constructive future – one that also can reap rewards for the public and Ohio. And keep a criminal record from turning into a lifetime punishment.

“I think we should be trying to make it a little easier for people to come back and be productive citizens after a conviction,” Werner said.

For Vicky in Franklin County, she has submitted her applications to expunge those long-ago criminal records that have tamped down her potential, and her hopes. Decades into her recovery, she has come so far. Now she waits.

She told the help center staff that if the court approves her application, she wants to go back to school to become a nurse. The end of her story hasn’t yet been written. But she welcomes a chance to close the door on her past and explore the prospects that await on the other side.

CREDITS: