New Hearing Ordered for Akron Man Given Death Penalty for Murdering Girlfriend’s Parent

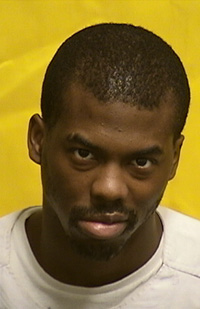

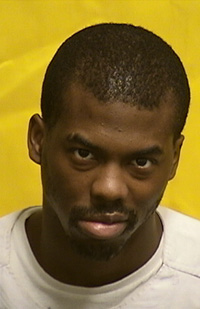

Death row inmate Shawn Ford Jr.

Death row inmate Shawn Ford Jr.

The Ohio Supreme Court today unanimously affirmed the murder convictions of an Akron man who admitted to killing his girlfriend’s parents with a sledgehammer. But the Court ordered a new hearing to determine if the man has an intellectual disability that bars the state from imposing the death penalty for one of the murders.

The Court ruled 5-2 to vacate Shawn Ford Jr.’s death sentence for the aggravated murder of Margaret Schobert. The Court determined the trial court used a standard developed in 2002 to find Ford was not intellectually disabled and that, based on U.S. Supreme Court decisions in 2014 and 2017, the trial court failed to use an updated standard to evaluate Ford.

Writing for the Court majority, Justice Melody J. Stewart stated the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that intellectually disabled individuals cannot receive the death penalty. The U.S. Supreme Court has adopted newer diagnostic standards from the leading American psychological associations, and those standards must be used to evaluate Ford, the Court ruled. Ford was 18 years old at the time of the 2013 murder and diagnosed in the “low average range of intelligence” at the onset of his trial.

“Under these circumstances, we have no confidence in the trial court’s determination based on its application of an improper standard,” she wrote.

The Court remanded the case to the trial court for further proceedings.

Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor and Justices Judith L. French, Patrick F. Fischer, and Michael P. Donnelly joined the decision.

Justice R. Patrick DeWine concurred with the majority in upholding Ford’s conviction, but dissented to state that the death penalty was justified. He wrote that three experts evaluated Ford’s intellectual ability after he was sentenced to death and all concluded he was not intellectually disabled.

Justice Sharon L. Kennedy joined Justice DeWine’s opinion.

Teen Stabbed, Parents Discovered at Home

Chelsea Schobert began dating Ford in 2012 and, in March 2013, she celebrated her 18th birthday with Ford and two others at a friend’s Akron home. They all began drinking and became highly intoxicated. Ford and Chelsea went to a bedroom, and Chelsea later said Ford wanted to have sex with her, but she refused. At one point she told him, “I hate you,” and he hit her in the head with a brick. One of the friends heard the encounter and went to the bedroom to intervene. Ford left the room, returned with a knife, and stabbed Chelsea in the neck and back.

Ford then drove Chelsea to a hospital, where they learned she suffered a spinal injury from the assault that had lasting effects. Ford, Chelsea, and their friends initially agreed to mislead the police about the incident and claim that Chelsea was assaulted at a party in Kent.

As police investigated the incident, Chelsea was placed in a secured area of Akron Children’s Hospital, and her parents, Jeffery and Margaret, did not permit Ford to visit her.

On April 1, Jeffrey Schobert left the hospital to return to their home in New Franklin, an Akron suburb near the border of Portage County. His wife Margaret remained with Chelsea until about 6 a.m. the next morning. That afternoon, a building contractor working on the Schobert’s home found Jeffrey’s and Margaret’s bodies in their bedrooms. Both had massive head wounds. A sledgehammer was lying on the bed next to Jeffrey, and his car was missing. Medical examiners determined that Jeffrey died from being struck at least 14 times with the sledgehammer and Margaret died from at least 19 blows with the hammer.

Suspect Lies, Later Confesses to Killing

At the time the bodies were discovered, Portage County authorities already had issued a warrant for Ford for lying about Chelsea’s assault. New Franklin police learned about Chelsea’s attack and her parents preventing Ford from seeing her in the hospital. They questioned Ford, who denied involvement, and took him to the Portage County jail.

The next day, police were informed that a fellow inmate of Ford’s learned the location of Jeffrey’s car, and police discovered it along with gloves, a knife, and a knit hat inside a storm drain in front of a house where a friend of Ford’s lived. Police discovered one of Margaret’s watches in the friend’s bedroom.

On April 3 and 4, detectives interviewed Ford and told him about the evidence they uncovered, and Ford eventually confessed to killing the Schoberts, and stealing money, jewelry, and the car.

On April 5, Ford made a recorded phone call from the Summit County jail to his brother, and discussed the murders during the call.

DNA and forensic testing showed that Margaret and Jeffrey’s blood was on shoes and clothing belonging to Ford.

Jury Convicts of All Charges

Ford was charged with five counts of aggravated murder and six other charges, including aggravated robbery, and the felonious assault of Chelsea. The jury convicted him of all charges and unanimously recommended the death penalty for the murder of Margaret.

Prior to the trial, the judge conducted two pretrial hearings to determine if Ford was competent to stand trial and whether he was intellectually disabled. He was found competent and not intellectually disabled. After the jury returned the death verdict, Ford’s attorneys asked the Court to dismiss the death sentences, and the court conducted a hearing to determine if Ford was intellectually disabled. The judge ruled Ford was not disabled, and affirmed the death penalty.

Death penalty convictions are automatically appealed to the Ohio Supreme Court. Ford raised 23 objections, known as propositions of law, to his convictions and sentence. The Court overruled nearly all of them, but in a few cases found errors by the trial court. Those errors were determined to be harmless and they would not affect the outcome of the guilt phase of the case, the majority opinion stated, because of the overwhelming DNA evidence and Ford’s confession.

Court Examines Intellectual Disability Determination

Justice Stewart explained that after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2002 that executing intellectually disabled persons violated the U.S. Constitution’s Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment, states were charged with developing appropriate ways to enforce the restriction.

The Ohio Supreme Court established its criteria in its 2002 State v. Lott decision, which defined an intellectual disability as “(1) significantly subaverage intellectual functioning, (2) significant limitations in two or more adaptive skills, such as communication, self-care, and self-direction, and (3) onset before age 18.” Lott also stated that a person is presumed not to be intellectually disabled if their intelligence quotient (IQ) is above 70.

In 2010, the American Association on Intellectual and Development Disabilities updated its medical diagnostic standards, and the American Psychiatric Association followed in 2013. The new definition of intellectually disability now recognizes that an IQ score should not be viewed as a fixed number, but a range within a statistical margin of error. And instead of finding a deficit in two or more adaptive skills, a disability could be a deficit in one or more activities of daily life.

In its 2014 Hall v. Florida and 2017 Moore v. Texas decisions, the U.S. Supreme Court adopted the updated standards for determining a disability. Today’s majority opinion stated that Ohio courts must also use this updated standard to determine the intelligence of an offender sentenced to death.

Early Scores, Adaptive Skills in Question

Three experts — one representing the prosecution, one representing Ford, and another appointed to assist the court — testified at the hearing after the jury voted for the death penalty.

The court’s expert conducted a detailed review of Ford’s school records and evaluations and found he was never diagnosed as intellectually disabled, but was found to have a learning disability. The expert examined five IQ tests administered to Ford between ages 6 and 19 and found scores that ranged between 62 and 80.

The expert also examined an adaptive skills test he took in third grade and she conducted her own test, as well as interviewing and observing Ford, interviewing his mother, and reviewing school achievement tests. She found no significant deficits in his adaptive skills.

The prosecution’s expert gave Ford an IQ test in which he scored a 79, and he received a score on the adaptive skills test that indicated his daily living skills fell in the “moderately low range.” The expert concluded there were not significant deficits in his adaptive functioning and he was not intellectually disabled.

Ford refused to be interviewed by the expert hired by his defense attorneys, but the doctor was able to review his records and meet with his mother. The expert testified that Ford scored a 75 on an IQ test he took in 2006 when he was 12. With the updated margin of error, Ford’s actual IQ could have been between 69 and 83, meaning he could be below 70. The expert discounted the two other tests where Ford scored below 70 because of his impulsive behavior and poor attention.

The defense expert also looked at Ford’s adaptive skills test and found a 2003 score that was between “mild mental retardation and borderline intelligence.” After having Ford’s mother complete an assessment of her son in 2013, the expert found Ford’s score was below average for social behavior. The expert testified that there was insufficient evidence to conclude Ford was intellectually disabled.

Trial Court Directed to Re-Evaluate Evidence

The majority opinion stated that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that when an IQ test score is below 70 and when adjusted for the margin of error, the score alone is not enough to determine the question of disability. The trial court must examine the other areas, including the adaptive skills, to adequately test Ford’s ability, the Court said.

The trial court failed to consider that Ford had a score in the range of 69-83. In addition, the Court noted Ford scored a 78 on a 2001 IQ test when he was age 6 or 7. Adjusting for what is known as the “Flynn Effect,” in which IQ scores appear inflated if an older test is administered, the Court also noted the test Ford took in 2001 was developed in 1983. One of the experts explained his score could have been inflated by 6 points, meaning his “fixed score” on that test was a 72. If the trial court were to examine the 72 score using the margin of error it could find a second score below 70, the experts maintained.

The majority opinion stated the trial court is not bound to recognize the Flynn Effect, but must discuss it in its new finding regarding Ford’s abilities.

The Court also noted that by using the Lott test, the trial court evaluated Ford’s abilities based on the fact that no expert diagnosed him with “two or more” adaptive skills deficits. The new standard requires a finding of only one deficit, and the defense’s expert raised questions as to whether Ford had a social behavior deficit, the opinion noted.

“Accordingly, we remand this matter to the trial court to properly determine whether Ford is intellectually disabled,” the opinion concluded.

Experts Ruled Out Disability, Dissent Stated

In his concurring and dissenting opinion, Justice DeWine explained the burden of proof was on Ford to demonstrate he was intellectually disabled and “he came nowhere near meeting his burden.”

The opinion noted Ford’s own expert was “hamstrung” by Ford’s refusal to allow him to conduct an interview, but noted that on many prior occasions Ford was evaluated by educational professionals and psychologists and had never been given a diagnosis of intellectual disability. When his own expert testified there was insufficient evidence to conclude Ford had a disability, Ford did not challenge the conclusion, or argue that the expert used the wrong standard, the opinion stated.

Nor did Ford did object to the opinions of the other two experts.

“It’s not surprising, then, that the trial court found that Ford had not met his burden to prove he has an intellectual disability,” the concurring and dissenting opinion stated.

Justice DeWine wrote that while there is room for improving the test laid out in Lott, the evidence indicates that even under the new standards, Ford would not be able to prove he was intellectually disabled.

“Every expert opined that Ford does not have an intellectual disability. To remand this case in the face of such strong evidence is simply wrong as a matter of law,” the opinion stated.

2015-1309. State v. Ford, Slip Opinion No. 2019-Ohio-4539.

View oral argument video of this case.

View oral argument video of this case.

Please note: Opinion summaries are prepared by the Office of Public Information for the general public and news media. Opinion summaries are not prepared for every opinion, but only for noteworthy cases. Opinion summaries are not to be considered as official headnotes or syllabi of court opinions. The full text of this and other court opinions are available online.

Acrobat Reader is a trademark of Adobe Systems Incorporated.